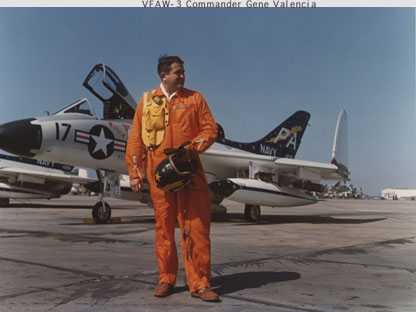

Eugene Valencia

![]()

The heaviest losses of U.S.

warships occurred in the last year of the war, due to Japanese kamikaze attacks. In the

first three months of the suicide attacks (from October 25, 1944), the kamikaze pilots

damaged 50 American ships. They continued in large numbers until the very end of the war.

On April 16 alone, during the Okinawa campaign, over 100 kamikaze attacks were launched,

sinking the destroyer Pringle, and hitting 11 other ships. Among the badly damaged

was the Intrepid, with a 12 by 14 foot hole in the flight deck, 40 planes

destroyed, and 9 men killed.

The heaviest losses of U.S.

warships occurred in the last year of the war, due to Japanese kamikaze attacks. In the

first three months of the suicide attacks (from October 25, 1944), the kamikaze pilots

damaged 50 American ships. They continued in large numbers until the very end of the war.

On April 16 alone, during the Okinawa campaign, over 100 kamikaze attacks were launched,

sinking the destroyer Pringle, and hitting 11 other ships. Among the badly damaged

was the Intrepid, with a 12 by 14 foot hole in the flight deck, 40 planes

destroyed, and 9 men killed.

Aboard nearby Yorktown was the most successful fighter division (4 planes) of the war, known as "Valencia's Flying Circus". Eugene Valencia was born in San Francisco in 1921. He joined the Navy as an aviation cadet in mid-1941, and trained until April 1942. After a stint as an instructor, he was assigned to the USS Essex in February 1943. With the Essex, he scored his first aerial kills, shooting down 3 enemy planes over Rabaul, 1 over Tarawa, and 3 more over Truk.

At Truk, he spotted a weakness in the enemy's fighter tactics, from which he developed his famed "Mowing Machine." Returning to the States for more training, he recruited three promising pilot trainees to work with him: James French (who finished the war with 11 victories), Harris Mitchell (10), and Clinton Smith (6). They put in three times the number of required training hours, perfecting their technique. When this division and others of VF-9 were ready, they joined the carrier Yorktown, a part of Task Force 58. TF 58 was continuing the difficult Okinawa campaign, which the Japanese defended fiercely until June 21.

On the morning of April 17, VF-9 was flying Combat Air Patrol (CAP); Jap air attacks were expected. Before dawn Valencia and the other Hellcat pilots launched and began the climb to 25,000 feet. Patrolling to the north, Valencia had a good chance of encountering the Japanese. The Hellcats circled on reaching altitude, and continued uneventfully for an hour. But then Yorktown's radar room reported contacts to the north, which Smith soon spotted. "Tally ho! Bogeys! Three o'clock!"

The closest pilot, French (a wingman), headed toward them; the division has trained so that any one of them could take over. From ten miles out, the enemy seemed to number about 20 or 30. But as the distance closed, Valencia estimated 35 or 40. Closing further, French called out "There must be fifty of 'em!" French and Smith led the first diving attack, with Valencia and Mitchell as top cover. The enemy formation didn't react; French and Smith both fired and hit the bomb-carrying Franks, which disintegrated when their high explosives were hit. These two crossed and pulled up to cover Valencia and Mitchell, who then rapidly closed with the enemy gaggle and exploded two more Franks.

The four Hellcats then reversed direction, while the Japs continued on their southern course, gambling that they could reach the American fleet before the Hellcats decimated their planes. Valencia and Mitchell led the return, closed in, and exploded two more Franks. French and Smith repeated the well-practiced "Mowing Machine" and shot up two more planes. After this, the Japanese dispersed, and Valencia radioed "Break tactics. Select targets of opportunity." The Franks, Zekes, and Oscars scattered widely, and Valencia's division split into pairs, pursuing as well as they can. To his relief, some other Hellcats joined the interception, as the Japs were closing in on the Yorktown. Valencia got onto another Frank's tail, and opened up from one hundred yards. Smoke streamed back and the Frank exploded. Victory number 3 for Valencia! So far his division had scored nine kills and two probables!

Valencia spotted three other Franks, and was briefly distracted by tracer fire, which turned out to be from Mitchell. Recovering, Valencia walked up on his fourth victim, and fires. Valencia stayed with his smoking target, while Mitchell clobbered another Frank from the same trio. Soon these two went down, upping the division's total to eleven, and Valencia's to four. Maneuvering, he then went for the remaining plane in the division, and poured shells into it. Victory number 5! All over the sky, American planes were downing the Japanese attackers. Valencia spotted a Frank on the tail of two unsuspecting Hellcats (intent on their own intended victim), and he picked up some speed, came within range, and pulled the trigger. His win number 6 saved the other Hellcat pilot. By now his division has racked up 14 kills.

At this point, low fuel forced Valencia to head back for the Yorktown. He rendezvoused with Mitchell, and circled, hoping to pick up French and Smith. A stray Jap fighter came too close, and Valencia stood on a wing and made for him. But as he pressed the trigger, nothing happened. His guns were empty! Valencia radioed the Yorktown and received permission for him and Mitchell to land. They thumped down their dirty, but unhurt fighters, followed shortly by Smith and French. The division had scored seventeen confirmed kills and four probables, their best day of the war.

The Flying Circus continued its deadly work. Seventeen days later, they knocked

down eleven enemy aircraft. Then on May 11, they scored another 10 kills, all in defense

of the fleet. By the end of the war, all had become aces, Valencia leading them with 23

kills, and receiving the Navy Cross for his heroism and

leadership.

Valencia went on to lead VF(AW)-3 as a full Commander. Under his leadership

as Executive Officer the unit twice won NORAD's highest honors for efficiency and

readiness, winning over all other NORAD squadrons, all of which were US Air Force units.