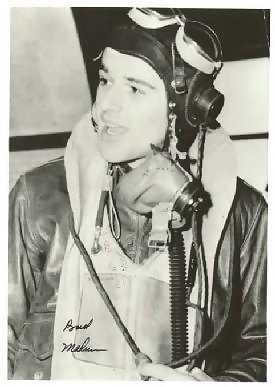

Col. Walker 'Bud' Mahurin

![]()

During WWII, Col. Walker

"Bud" Mahurin was the first USAAF double ace in Europe and the first recipient

of the Silver Star in the famous 56th

Fighter Group. Flying the rugged P-47

"Razorback," Col. Mahurin was competing for the group's "top aces"

position when on March 27, 1944, Mahurin shot down a Dornier Do 217 bomber. His P-47 was

hit and set afire. Mahurin bailed out and spent several adventurous months with the French

underground before being flown back to England in an antique plane operated by the

underground. Because of his knowledge of the underground, he was not allowed to continue

flying combat over Europe and was sent home. By pulling all the strings he could reach,

Mahurin got an assignment as commander of the 3d Fighter Squadron, 3d Air Commando Group,

which was about to deploy to the Pacific. By early 1945, there were few enemy fighters

left in the Philippines. Mahurin did down one of them, ending the war with 20.75 confirmed

victories even though his time in the hunting grounds of Europe had been cut short a year

before that war ended. He had the unique distinction of being forced to bail out in both

theaters.

During WWII, Col. Walker

"Bud" Mahurin was the first USAAF double ace in Europe and the first recipient

of the Silver Star in the famous 56th

Fighter Group. Flying the rugged P-47

"Razorback," Col. Mahurin was competing for the group's "top aces"

position when on March 27, 1944, Mahurin shot down a Dornier Do 217 bomber. His P-47 was

hit and set afire. Mahurin bailed out and spent several adventurous months with the French

underground before being flown back to England in an antique plane operated by the

underground. Because of his knowledge of the underground, he was not allowed to continue

flying combat over Europe and was sent home. By pulling all the strings he could reach,

Mahurin got an assignment as commander of the 3d Fighter Squadron, 3d Air Commando Group,

which was about to deploy to the Pacific. By early 1945, there were few enemy fighters

left in the Philippines. Mahurin did down one of them, ending the war with 20.75 confirmed

victories even though his time in the hunting grounds of Europe had been cut short a year

before that war ended. He had the unique distinction of being forced to bail out in both

theaters.

Korean War

In December, 1951, he arrived at Suwon AB, South Korea on temporary duty assignment and became special assistant to the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing's commanding officer, his old friend Col. Francis S. "Gabby" Gabreski.

Col. Mahurin helped Gabreski develop tactics and solve logistics problems and was able to squeeze in some combat action. He shot down two MiG-15s and later was credited with 1.5 more, bringing his total to 24.25 and becoming the only Air Force pilot with victories in the World War II European theater of operations, Pacific theater, and Korea. Before his 90-day TDY was up, he was given command of the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing at Kimpo AB, South Korea. His call sign was "Honest John." Col. Mahurin scored 3 1/2 victories flying the F-86 in Korea.

On May 13, 1952, his aircraft was hit by ground fire and he was forced to crash land in North Korea, breaking an arm. Taken prisoner, he was confined to a small cell and fed only enough water and food to keep him alive.and subjected to brainwashing, a new brutality unknown to the free world. He was forced to endure sub-freezing conditions with minimal clothing, intorrgations sometimes lasting all night while standing at attention, deprived of sleep and threatened with execution if he did not answer questions. The North Koreans were adamant that he sign a confession that he and the US had waged "germ warfare" even though the North Koreans knew this to be false. After weeks of psychological and physical torture, Col. Mahurin, believing he was losing control, attempted suicide but was discovered before he was able to complete the act. He barely survived a tremendous loss of blood.

The interrogators finally gave up, to be replaced by a well-educated Chinese officer who spoke fluent English, brought Mahurin books, arranged for better food, and generally improved his conditions. Eventually the Chinese officer's real purpose emerged-to get a confession of germ warfare by persuasion rather than threats. He reminded Mahurin that the allies did not know he was a POW, so he could be held until his death, never to see his wife and children again. Bud Mahurin at last agreed to write a "confession" so full of inaccuracies and implausible information that any Western reader would know it was fiction. Unknown to him, the war had already ended.

After his release from confinement in 1953, Col. Mahurin's willingness to discuss brainwashing techniques and psychological pressures applied to American POWs greatly aided the content of Air Force survival courses. Upon return to the States, Bud Mahurin and other former POWs were shocked to learn that some Americans, including Sen. Richard B. Russell (D-Ga.), thought that those who signed confessions should be discharged under conditions other than honorable. The Defense Department thought otherwise. All but four who had signed confessions were cleared of wrongdoing by a board of senior Air Force officials.

Colonel Mahurin was assigned as vice commander of the 27th Air Division. Because of his position on the promotion list, it seemed unlikely that he would be promoted to regular colonel and be considered for a star and a higher command in his remaining years of service. He therefore resigned his commission in 1956 to accept a senior position with the aircraft industry. Later he joined the Air Force Reserves, subsequently retiring as a Colonel.

Portions by John L. Frisbee,

Contributing Editor Air Force Magazine